|

| Manifest of the John Murray (click to enlarge) |

|

| Limerick Pier about 1870 |

November, 1848 found the John Murray in Limerick, Ireland. Notice the advertisement at the right in the Limerick and Clare Examiner on November 8th.5 I have

not found any other

movements for the ship, so, this may have been her second

voyage. Notice the description of the

ship – “First-Class Coppered Fastened Barque” of 700 tons burthen. Also, notice that the ship was being fitted to

carry passengers where she had carried cargo on her previous and subsequent

voyages. What is a barque, how large was

the ship, and what accommodations did the family travel in?

|

| Ad from Limerick and Clare Examiner 8 Nov 1848 (click to enlarge) |

A barque refers to the type of

ship and rigging used. A typical barque

is shown in the picture below left.6 A

barque contains three (or more) masts with square rigged sails on all but the

mast

at the stern (rear) of the ship.

The mizzenmast is “fore-and-aft” rigged with the sail running parallel

to the keel. Copper sheating was

applied to the under-water portions of the hull to protect it from corrosion.7 A “burthen” of 295 or 700 tons

does not refer to the weight of the ship but to cargo capacity.8

|

| Unidentified barque |

Several years ago, while visiting

Ireland, we stopped by the Dunbrody9 docked

in New Ross. I asked the staff at the

museum if an estimate of the dimensions of a ship could be made based on the

burthen given. Evidently there are a lot

of variables including the age of the ship, type of lumber used, the design and

method of construction. “Burthen” (or

tons) is not a good indicator of what the ship looked like. Even so, I did attempt to find dimensions for

a barque of roughly 300 tons. The

average appears to be 106 feet long, 25 feet at the beam, and 15.5 feet in

depth.10

The average trip to America from

Ireland was six weeks or about 35 days.

That would probably have been a summer voyage. The Browne’s made a winter crossing, which

made for a much different journey. The John Murray left Limerick for Boston on

November 15, 1848. Several newspapers,

including the Athlone Sentinel and the Tipperary Free Press, carried news of her departure. They also described the 130 passengers as

“mostly of the better class of peasantry.”11 The John

Murray arrived in Boston on January 26, 1849, a journey of 72 days - double

the average. I have not been able to

find other ports that the John Murray

may have visited on that voyage to explain why it took so long to reach Boston;

however, I have found information on the final stages of the journey.

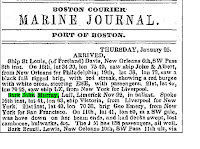

The Marine Journal report in the Boston Courier for January 29, 1849 ran

a story that on January 11, 1849, “ in a

SW gale, [the John Murray] was hove

down on her beam ends, and had decks

swept, lost camboose, bulwarks, &c.”12 (See image at left.)

Several other ships in the vicinity also reported damage to masts and

cargo. One report stated the storm raged

for two days.13 In the same newspaper on the same date, under

the heading “Died” is reported, “Lost overboard, January 11, during a S.W.

gale, from bark John Murray, on the

passage from Limerick to this port, James Davis, cook, (colored) of Exeter, N

H., aged about 40.” A camboose [caboose]

is the nautical term for a ships galley, or kitchen, on an open deck.14 Mr. Davis was obviously at his post

during the storm that took his life.

|

| Marine Journal Boston-29 Jan 1849 (click to enlarge) |

What an absolutely terrifying

time that must have been! While all of

the passengers were likely below deck with the hatches battened down, water

still poured into the hold as the decks were washed with water soaking everyone

and everything. I’m also sure the passengers could have heard

the commotion of the

sailors on deck battling the storm and poor Mr. Davis

being washed overboard which added to their terror. With each roll of the ship, people and

belongings would have been tossed about like sacks of potatoes hitting bunks,

and other passengers, lining the sides of the hold. While no one died on the voyage, (according

to the passenger list), there were likely injuries to many of the occupants –

bumps and bruises and probably broken bones if not worse. (See picture of hold above16)

|

| Passenger bunks Dunbrody |

We have some idea of what those

two days on the ship were like; we don’t know about the other seventy days. They still had two weeks before they reached

Boston and had already been on the ocean 57 days. The John

Murray ads in the newspapers always catergorized her as

“fast-sailing.” What else happened on

the voyage to make it take so long? American

ships carried more and better rations, but, after so many days at sea, what

food supplies were left, and, were they damaged in the storm?

The ship nearly capsized, and

probably would have had the ship not been new and strong. Equipment on a new ship would have been in

better condition. An older ship, where

the timbers were weakened by age, probably would have broken apart and everyone

would have been lost. The competency of

the crew also added to the outcome of the crossing. Sailors on American ships earned higher wages

and were better seamen.15 So,

while we initially questioned why an American ship was chosen over a less

expensive British ship to Canada, I think we can be very glad they did or there

may not be a story for the Browne family to be told.

The next post will tell of the

early days of the family in America.

P.S. While I was doing research for this post, I

discovered that the whaling ship, Charles

W Morgan built in 1841 in Massachusetts and docked at Mystic Seaport in

Connecticut, is also a barque. Although

she had more cargo capacity and was never used as a passenger vessel, the outer

dimensions are roughly the same as the John

Murray. The website for Mystic

Seaport has information on the restoration of the Morgan which contains a couple of short film clips showing her

under full sail in 1921 before she was retired and after restoration in

2014. You might find the clips

interesting. http://www.mysticseaport.org/visit/explore/morgan/

1.

Passenger List, NARA "Massachusetts, Boston Passenger Lists, 1820-1891." Database

with images. FamilySearch.

http://FamilySearch.org : John Murray

January 26, 1849; Citing NARA microfilm publication M277, Roll 28,

Washington D.C.; National Archives and Records Administration

2.

“Boston

Daily Atlas Marine Journal – Domestic Ports – Bath.” Boston

Daily Atlas, Boston, Massachusetts, October 23, 1847, Online Nineteenth

Century U.S. Newspapers available through the Cincinnati Public Library,

Cincinnati, Ohio.

3.

“Marine

Journal.” Boston Daily Atlas, Boston,

Massachusetts, Online Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers available through the

Cincinnati Public Library, Cincinnati, Ohio; November 16th and 23rd,

1847; February 24, 1848, April 1, 1848, June 12, 1848, and July 26, 1848.

4.

Picture of

Limerick harbor, 663, Ancestry.com. Ireland,

Lawrence Collection of photographs, 1870-1910 [database on-line]. Provo,

UT, USA; Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

5.

Advertisement,

Limerick and Clare Examiner, November

8, 1848, Find My Past, online at http://search.findmypast.com/bna/viewarticle?id=bl%2f0000824%2f18481108%2f023

6.

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and

Photographs, digital ID det.4a25817, Unidentified

sailing ship., http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/det.4a25817. Other copies of the image have identified the

ship as the Salmon P Chase built

1878. She was 142 tons at 115 feet in

length and 25 feet wide.

7.

Glossary of

Nautical Terms, Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_nautical_terms

8.

Builder’s

Old Measurement, Wikipedia, online at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Builder%27s_Old_Measurement

There are several methods of measuring capacity using the length, width

(beam), and depth of the ship.

Historically, a ton (tun) was a wine container of 252 gallons that weighed

about 2,240 lbs (a long ton). A ton

averaged 100 cubic feet. The number of

containers that a ship could carry determined the “ton” capacity of the ship. The large discrepancy between the capacity

shown in the advertisement (700 tons) and that shown when the John Murray reached Boston (295 tons)

may have been an attempt to fill the ship with more passengers than allowed

even though the Limerick agents were aware of new American regulations as

evidenced in the text of the ad. (See

previous post, Arrival in America, for

discussion of the 1847 shipping regulations.)

9.

The original Dunbrody was built in 1845 in Quebec. She was 458 tons and measured 110 feet long,

26 feet at the beam, and 18 feet deep.

From 1845 until 1851, she carried anywhere from 160 to over 300

emigrants on each voyage from Ireland to Canada. The ship that can be visited today is a

replica of the original. More

information on the Dunbrody is

available at http://www.dunbrody.com/visitor-info/the-history-of-dunbrody/

10.

Lloyds of

London Register of Ships gives a listing and description of ships sailing from

British ports. It is available online

at http://www.lrfoundation.org.uk/public_education/reference-library/register-of-ships-online/ .

Beginning in 1863, in addition to tonnage, the registry began recording

dimensions of the vessels. To obtain an

average, I looked at the 1863 registry for “barques” built in the 1840s that

were between 280 and 320 tons. While

there were many such ships, I limited my calculations to fifteen randomly

selected ships in that group. The John Murray was not shown in the

registry for any year, perhaps because it was an American ship.

11.

Athlone Sentinel, November 22, 1848, page 3. Available online at Find My Past.

12.

Marine

Journal, Boston Courier, Boston, Massachusetts,

January 29, 1849, Online Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers available through

the Cincinnati Public Library, Cincinnati, Ohio.

13.

Reports for

the Avon, Fanny, and Leander in the

Boston Courier in the February 1st

and February 8th issues tell of the damages sustained by those

ships. Online Nineteenth Century U.S.

Newspapers available through the Cincinnati Public Library, Cincinnati, Ohio.

14.

Glossary of

Nautical Terms, op. cit.

The phrase “on her beam ends”

indicated that the ship was above 45ᵒ or nearly vertical on her side.

15.

Woodham-Smith,

Cecil, The Greeat Hunger, Harper & Row Publishers, New York and Evanston,

1962, pp. 212-213

16.

Photo of the

hold of the Dunbrody, September,

2012, from the collection of the author. The bunks on the John Murray would have looked similar, although they were but

temporary structures while those on the Dunbrody

were permanent. Each bunk was shared by

four adults, more if there were children.

Also, there may be more headroom on the Dunbrody than on other ships that had temporary living quarters.